Heatmap

What is a heatmap?

A heatmap is a graphical representation of data that uses a system of color-coding to represent different values. Heatmaps are used in various forms of analytics but are most commonly used to show user behavior on specific webpages or webpage templates. Heatmaps can be used to show where users have clicked on a page, how far they have scrolled down a page or used to display the results of eye-tracking tests.

Benefits of heatmaps

Analytics tools like Google Analytics or Site Catalyst are great at providing metrics to show which pages users visit, but they can lack detail when it comes to understanding how users engage with those pages. Heatmaps can give a more comprehensive overview of how users are really behaving.

Heatmaps are also a lot more visual than standard analytics reports, which can make them easier to analyze at a glance. This makes them more accessible, particularly to people who are not accustomed to analyzing large amounts of data.

Good heatmapping tools, such as CrazyEgg, enable analysts to segment and filter the data. This means that it can be easy to see how different types of users are engaging with a particular page.

Considerations

Like most forms of web analytics, heatmaps need to have a large amount of data before they can be accurately analyzed. Analyzing heatmaps based on a small amount of data is similar to ‘calling’ A/B tests too early, based on too few visits or conversions. As heatmaps show trends, it is important to have enough information to ensure that any anomalies do not affect the overall heatmap picture.

When used incorrectly, heatmaps can be misleading. They can encourage analysts to make assumptions that may not be correct. It is important to remember that, as with other forms of quantitative data, heatmaps can tell you what has happened on a page, but cannot tell you why that happened.

It is also important to be aware of the limitations of heatmaps. Often, heatmaps will show clicks on a page (known as click maps) but this may only be a part of the story. For example, when looking at a heatmap of a form, it may show that users are clicking on the first field and that there are fewer clicks on the subsequent fields.

This could suggest that users are dropping out of the process after filling out the first field. What heatmaps do not show, however, is if users have used their keyboard to tab through form fields, rather than their mouse. To correctly analyze form usage, dedicated form analytics tools can be used. These will measure the time spent within each field, rather than just clicks.

Heatmap examples

Heatmaps provide a good way to see, at a glance, how ‘popular’ the elements on a certain page are. This is particularly useful for comparing elements that are given similar prominence on the page. The heatmap below shows where users clicked on a product page of mobile phones:

It is clear to see from this that the current order of these phones does not match their popularity. Users are often choosing the highlighted phone, despite it appearing quite far down the list and ‘below the fold’ on most devices. One possible solution to this would be to display the phones in order of their popularity to save users from having to scroll to find popular phones.

Heatmapping can be also be useful for differentiating between links when there is more than one link on a page that goes to a particular destination page. Some analytics tools, such as Google Analytics, treat links to the same destination as the same link. This makes it impossible to tell which of the links has received the most clicks.

One example of where this differentiation is useful is determining how many people are using the links in your footer compared with those in your main navigation. This is often more than you’d expect!

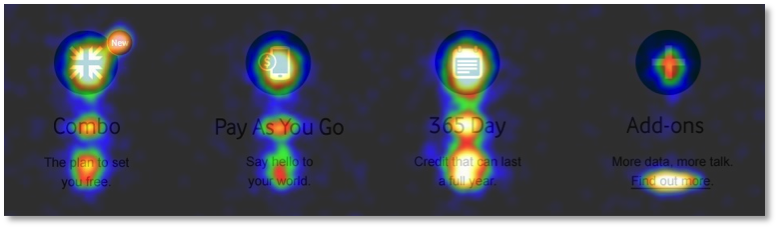

Heatmaps can be used for identifying clicks on parts of a page that are not actually links. In the example below, only the ‘find out more’ text is a link, yet users are erroneously clicking on the icons in an attempt to get more information.

This shows clear user intent and suggests that these icons should in fact link to more information about each of the options.

Scrollmaps show which part of your content is the most engaging and how far down a particular page your users are reading. Scrollmaps won’t show you what users have read but can highlight areas where users are scrolling past (i.e., not reading) content that you may feel is important. If you have a blog and the scrollmap shows that the majority of the time is spent at the start of an article and very little is spent towards the end, then you might want to focus on making your blog posts shorter, or more engaging!

Final thoughts

Heatmaps will not answer all of your questions about how users are engaging with your website but they can give insight that is not readily available from other analytics tools. As long as they are used in the right way, and conclusions are not drawn from small amounts of data, then heatmaps can be a highly effective weapon in the web analyst’s arsenal.

Using heatmaps during the discovery phase of your CRO campaign can really help to identify additional areas for testing. The examples provided in this page have all been used to inform A/B tests on changes to page layouts and functionality to better match user intent.

Heatmaps can also be integrated with A/B tests within Optimizely. This means that you will be able to get a clear picture of how users are engaging with your test variations compared with your original.